“Liberty and justice for all…” Those are the words that define America. The land of opportunities and the place of prosperity; the land in which social mobility is possible and everyone is free. That is the driving force behind our government: to secure “liberty and justice for all.” However, the grass is not greener on the other side. Once you enter the nation the disparities in this “liberty and justice for all” become apparent. There is a big division and a more accurate statement is “liberty and justice for some.” To maintain its status as a world power and a desirable nation, the United States creates the illusion -to its spectators- that the country does not have a divide, that it does not see individuals as “others” but instead, that they are all equal.

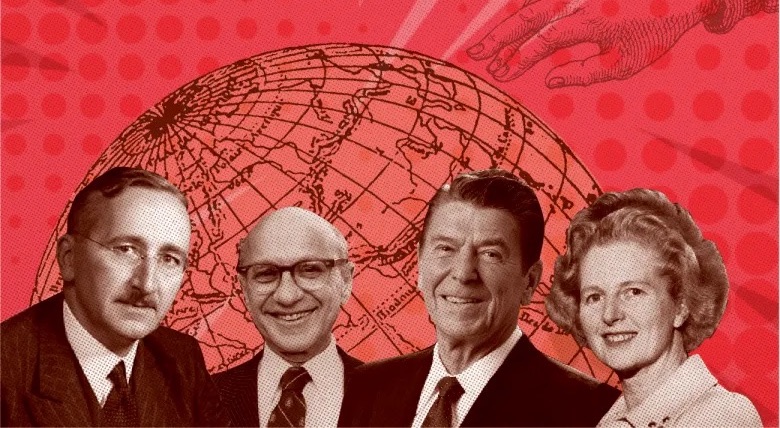

The United States prides itself on having its citizens pull themselves up from their bootstraps. Its citizens are superior and this gives them the power to move into other nations and requires that the nations submit themselves to the guidance and “advice” of the superior country. This is something that Wendy Brown touches on in “Neoliberalism and the End of Liberal-Democracy”, which establishes how the elitist culture of the United States attempts to erase the intersectionality of race, gender, and other identities when it drafts policies. She emphasizes how the nation now focuses on the profit-maximizing aspects of policy and generates policies that will create what they deem as “prudent” citizens who can thrive and increase the GDP of the nation (43). Through this, the nation no longer has to worry about its own and rather seeks to expand its market power, thus, the economy becomes the driving force behind the politics of the nation, and anything or anyone that threatens its success and survival must be gone.

Upon closer examination we see how the neoliberal agenda furthers the creation of the good citizen and the bad citizen - even goes as far as to call it the good person v. the bad person. The good person is the one that is “self-caring,” who can provide for their needs and seek out their dreams; it is that who sustains and contributes to the economy. The bad person is that who needs “handouts;” it is that who is incapable of caring for themself and becomes a burden to the state.

These distinctions alter the structure of the nation, the GDP can not increase if those who are good are held back by those who are bad. The good and the bad cannot co-exist, they must not interfere with each other. The bad can see the good but the good cannot see the bad. This is something that Frantz Fanon demonstrates in his chapter “On Violence.” The United States (being a colonized and colonizer nation) has the separation and creates the characteristics of what it means to be good and what it means to be bad. To be good is to be hardworking, to be bad is to be lazy, to be good is to be clean, to be bad is to be dirty, to be good is to have money, to be bad is to beg for money, to be good is to be a policeman, to be bad is to be policed, to be good is to be white, to be bad is to be non-white (4). The nation needs to find a way to deal with all these people who due to their lack of whiteness are not destined to advance the economy, rather they are burdens to the state because their inferiority deems them incapable of success. They are sources of labor as opposed to managers and creators of labor.

Activist and abolitionist Angela Davis discusses the necessity for free labor under the neoliberal capitalist economy. In her book Are Prisons Obsolete? Davis discusses how businesses benefit from the massive source of labor that comes from incarcerated individuals; the businesses make their products and pay a fee to the states to maintain the prison facilities running. Through this, the profitability of these companies depends on the “otherization” of incarcerated individuals. This is where we see Fanon’s dichotomy of the makeup of a colonized nation intersect with Davis’s thoughts, individuals behind bars are criminals and they are better off disconnected from the “good” society that is deserving of their freedom. To conduct the prison state, the “good” public must not see the “bad” individuals, they must be cut off from society and that isolation must be justified. Thus, Davis establishes “in the United States race has always played a central role in constructing presumptions of criminality” (28); like Fanon, she recognizes that it is an individual identity that ties them to crime rather than their action, this is obvious as she comments on the fact that individuals in Black, Latino, and Native American communities are far more likely to go to prison than to get a decent education (10). Non-white bodies -under this logic- are sources of labor, they are incapable of self-care and even less capable of revolutionizing the economy. Therefore, the state must do it for them, no matter what it takes.

The United States hides its non-white citizens from the world. These citizens are so evil that their existence should be banished as it can tarnish Uncle Sam’s reputation, and he certainly would not want that.

Works Cited

Brown, Wendy. Neoliberalism and the End of Liberal-Democracy. 2003.

Davis, Angela. Are Prisons Obsolete? 2003.

Fanon, Frantz. “On Violence.” Wretched of the Earth, 1961.