I carry their faces with me,

If you are quiet long enough

You can hear them whispering,

why? why? why?

Faces that smiled,

Graves unmarked,

Bodies destroyed,

Voices gone.

why? why? why?

Temptresses by nine,

Seductresses by sixteen,

Bitches by nineteen,

Whores by twenty-two

Dead by thirty.

why? why? why?"

Art has an obsession with women. The effortless grace and the femininity that accompanies them appear irresistible to artists. But the reality of women is not two-dimensional like the one depicted in the canvases that often portray them; women have to confront the world every single day. In the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), there are many masterpieces that focus on women. Observing these pieces, on the fifth floor of the museum, the collection of the 1880s-1940s, I noticed a pattern of nudity in the depiction of women. After viewing, The Aunts by Julio Castellanos, I felt inspired to write a poem in which I questioned “how does the nude depiction of women -by men- leave women vulnerable to the subjection of the male gaze?” I desired to examine this central idea of my poem with other art pieces and attempt to answer the question. The pieces I will examine in this essay are The Aunts by Julio Castellanos, The Dance (I) by Henri Matisse, and “Still I Rise” by Maya Angelou.

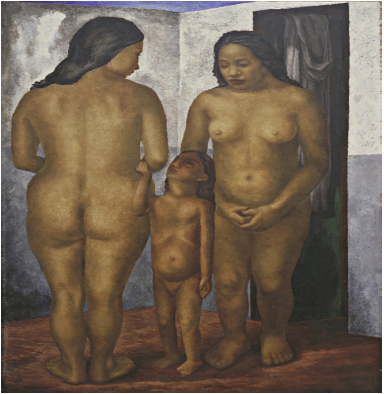

The Aunts

Painted by Mexican artist, Julio Castellanos, in 1933, the painting depicts a moment between two indigenous women and a child. Their caramel skin tone separates them from Europeans and their nudity renders them “uncivilized,” as it was typical to label indigenous individuals. Their hair is long and black and the waves at the end fall perfectly to frame the faces of the women. The three of them stand together, almost as if hearing each other in conversation. The woman to the left faces the wall, we only see her behind. Her body is curvaceous, highlighting her hips and emphasizing her small waist. To the right, this woman is facing forward with her bare chest explored, her arms carefully placed so as to cover her pubic area; she looks attentively at the child in the middle. The child has her left arm holding the woman to the left, almost as if to grab her attention. This child, unlike the older women, is not trying to cover up her body; she is focused on receiving attention.

In the final stanza of my poem, I focus on the progress of the views harbored towards women. In childhood, women are often called “too grown,” “too fast,” or “too mature for their age.” Women do not have the liberty to grow up without notions of how to preserve their purity.

Yet, kids do not know what purity is. Comments will be made questioning the child’s nudity, sexualizing her innocence with concepts of impurity; but, the child is not bothered by her body, she does not seek to cover it, and does not yet seek to protect it. Meanwhile, the women are not exposing their complete bodies, they cover themselves. Despite showing some parts of their body, the woman to the right still covers her pubic area, and the woman to the left does not bare her front side. Why did Julio choose to prevent the women from being depicted fully nude? My assumption was that he also recognized the narratives that -I described- follow women: “seductresses,” and “whores.” Moreover, the painting teases the viewer, the one who seeks the voyeuristic feeling from it, Castellanos shows them just enough to parade their bodies and their maternal abilities, he places them as unexpected temptresses who exist and grow in nudity, but utilize their bodies to protect their purity. Even in this seemingly mundane context, the women are viewed both as mothers and sexual beings.

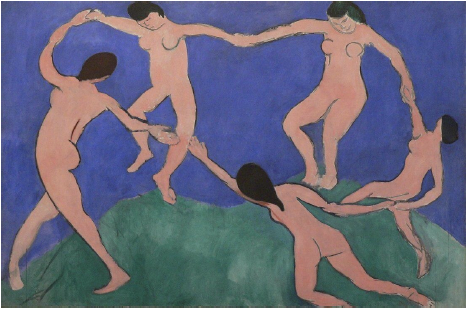

The Dance (I)

Henri Matisse created this as a model for a commission for a painting (Museum of Modern Art). Done in 1909, the painting depicts five women holding hands. The women appear to be in motion as their bodies demonstrate movement similar to that as if they were going around in circles. The outline of their bodies is fully marked, emphasizing their breast and their behinds. Their hair is black and varies in length. The background is extremely clear, half dark blue and half green. The women appear to be nude, as their bodies are colored pink, so as to simulate the pink undertones of white skin. Not all the women have faces, only the two on the left that are facing forward have lines that resemble eyes and a smile. The women are shown to be in an engaging activity, they are supposed to be radiating joy, and their cares are left behind as they dance with each other.

The actions of Matisse were premeditated, he choose to depict these women naked and joyous. As the audience, however, we peer into this scene and it almost feels as though we were not supposed to watch, the women are not preoccupied with anything, they are careless in their joy and in their nudity. Unlike the women in Castellanos's painting, these women do not attempt to cover their bodies, they are almost free in this expression of joy. In the second stanza of my poem, I describe what women whose lives were lost to patriarchal violence used to be, “Faces that smiled, graves unmarked, bodies destroyed, voices gone.” The women in this painting are those faces that smiled, they demonstrate the untainted happiness of being free. Yet, the depiction by Matisse of this state of Eden is lost by the audience observing it. Once again, the mere existence of these women is turned into an attraction for the viewer, their happiness is tainted by the lack of privacy of the moment, Matisse is not just depicting the women in a joyous state, he depicted them in a “sensual joy” in which the women moves smoothly, they almost fly in their movements. Their bodies are destroyed because, despite the evident movement, their breast remain perfect defying the laws of gravity, and their hands stretch at great lengths, which to me, ironically represents the great lengths at which women have to stretch themselves to survive the expectations placed upon them by society. The women are reaching for each other in order to survive, each of them “carry their faces” with them, and they are all one of the same. Matisse strips them of their individuality, their voices are gone because they are simply made to represent the joy that Matisse wants his audience to feast on.

“Still I Rise”

Does my sexiness upset you?

Does it come as a surprise

That I dance like I’ve got diamonds

At the meeting of my thighs?"

(Angelou, lines 25-28)

Maya Angelou wrote her poem “Still I Rise” in 1978. In it, she discusses the perseverance of African Americans in the face of oppression and social discrimination. My peer Elias Glitterman points out one of the main elements of Angelou’s poem: “Finally, Angelou's poem penetrates deeply into the spirit, as it seeps with confidence and defiance. Similarly to Harlem, the poem changes rhythm about two-thirds of the way to the end, which helps illustrate the picture of an African American woman's courage, strength, and sense of self.” In lines 25-28, Angelou owns her sexuality, she embraces her existence as a sexual being. She teases the audience and proclaims ownership over her body, she is attractive, despite attempts of society to make her believe otherwise. Unlike Castellanos’s painting, she does not cover the “diamonds at the meeting of her thighs,” she is not ashamed of her body, and she does not face the wall; unlike the women of The Dance (I), she is not ignorant of her sensuality, she does recognize the existence of it. The main difference between Angelou and the other paintings is that she is a woman, she is not writing about fantasy, and she does not speak of what women should be, but rather what they are.

In my poem, I write of the labels that the patriarchy places upon women, specifically establishing a mourning tone throughout the poem. Angelou, however, had a different tone; my peer, Jalal Hussain, establishes in his discussion post for Week 4, “ …the tone was "indignant" or "sassy" and believed that the message, in short, was that no kind of oppression or control can suppress someone's freedom to life (to live however one pleases regardless of what anyone says).” Angelou recognizes that sexiness is viewed as upsetting by society, she recognizes that women are not rewarded by the recognition of their sensuality. Her poem is a stance towards repression, mine is a statement about the consequences of oppression.

New Visions

The implication of the male gaze on the depiction of women is that there is no escaping from their patriarchal idea of what women are supposed to be. So to speak, all art created by men in which women are depicted is an extension of their fantasies about women and their ideas of what womanhood is. Women face the consequences of this art, they live in societies in which those ideas are upheld, and women are expected to be pure, yet sensual. Most women are able to break away from those ideas and express liberty in their artistic impressions of women. Yet, there are still some who maintain patriarchal notions. Is there a possibility to observe art depicting women made by men and fail to observe idealizing and patriarchal ideas? Is male art stuck in a perpetual cycle of reproducing these ideals?

Works Cited

Angelou, Maya, and CM Burroughs. “Still I Rise by Maya Angelou.” Poetry Foundation, 1978, https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/46446/still-i-rise. Accessed 17 November 2022.

Gitterman, Elias. Discussion Post Week 4. Discussion post week 4 for arts and culture modernity, section 025. Brightspace, 27 September 2022, https://brightspace.nyu.edu/d2l/le/203748/discussions/topics/346986/View.

Hussain, Jalal. Discussion Post Week 4. Discussion post for week 4 of arts and culture modernity, section 025. Brightspace, 26 September 2022, https://brightspace.nyu.edu/d2l/le/203748/discussions/topics/346986/View.

Museum of Modern Art. “Henri Matisse. Dance (I). Paris, Boulevard des Invalides, early 1909.” MoMA, https://www.moma.org/collection/works/79124. Accessed 17 November 2022.

Museum of Modern Art. “Julio Castellanos. The Aunts. 1933.” MoMA, https://www.moma.org/collection/works/78300. Accessed 17 November 2022.