Through globalization, the transition to democracy, and economic improvement, Spain has experienced a high level of people migrating. Through this migration, we notice the formation of ethnic communities and sectors around Spain. In Madrid, we see neighborhoods such as Lavapies, which is mostly composed of Senegalese and other African immigrants, and Tetúan, which is mostly composed of Dominican and Latin American immigrants. With the formation of communities like these, we see the shaping of neighborhoods into areas that provide cultural comfort to newcomers. The proximity to others of the same background and experiences allows for a sense of community to be built from the idea that the people around you will understand what it means to emigrate to Spain and the challenges it brings, as well as the benefits.

Cultural Organizations

However, in a new country, it takes more than a village for foreign people to integrate. Advocacy groups or migrant people support groups are key actors in the integration and advancement of these newcomers. An article published by the Ryerson Center for Immigration and Settlement defines the work produced by these organizations as the provision of “settlement services” (Shields et al, 2016). These services are focused on three key aspects of helping the migrant: 1) Adjustment: getting used to the host culture, language, people, and environment 2) Adaptation: Learning how to navigate and find resources in the host country independently 3) Integration: Social, cultural, and political participation in the host society (Shields et al, 2016). The existence of these organizations acts as a support system to connect newcomers with resources and people. At times, these organizations can be the main source of socialization and community that a migrant person has (Thomas et al, 2016). Thus, their existence is vital to the direction that the acclimation experience for migrants takes. Organizations that support migrant settlements tend to offer a range of services. They can range from connection to legal counsel, labor resources, childcare, language classes, and cultural exchanges (Gates, 2014). In the Spanish lens, these organizations are crucial to the day-to-day lives of over six million people (Ministerio de Inclusión, Seguridad Social y Migraciones, 2023) who seek to rebuild their lives in the country. These organizations are also known as “cultural organizations”

Cuban Migration

Since the Cuban Revolution in 1959, every year a large number of Cubans migrate to different countries to escape the economic hardship and political climate of the island. The colonial ties to Spain make the country a certain destination for many Cubans seeking to relocate. Not only is there a shared language, but there is also the institution of heritage laws that allow a secure pathway to citizenship for those Cubans who can prove that their grandfather or grandmother was of Spanish origin (Ministerio de Asuntos Exteriores, Unión Europea y Cooperación, 2022). This in turn has directed a large exodus of Cubans to the self-proclaimed “motherland” of the island.

In 2022, over 200,000 Cubans were recorded as living in Spain -the highest number reported by the Instituto Nacional de Estadísticas- many of whom gained asylum through the ‘grandkid law’ by the Law of Historical Memory. This influx of migration into Spain has given way for a strong network of Cuban communities to develop across the country. These communities bring with them the establishment of Cuban restaurants, religious stores, musical performances, and Cuban neighborhoods. As discussed in our reading “The Problem with Similarity: Ethnic-Affinity Migrants in Spain,” people who seek to relocate to new countries tend to have advantages if the nation of relocation perceives their culture as similar to theirs (Cook-Martín & Viladrich, 2009). Such is the case for Cubans who relocate to Spain. However, despite the similarities, the integration process into the new culture still requires systemic and social support. The support for the expansion and success of Cubans in Spain would not be possible without the help of cultural organizations.

Cuban Cultural Organizations & Current Questions

Since 2004, according to our reading “Madrid’s Intercultural Perspective” by Fabiola Pardo, Spain has prioritized integrating relocators in the country through integration policies (2017). These integration policies have given rise to cultural organizations, such as the Asociación Rumiñahui which focuses on helping Ecuadorians and other people of different backgrounds who relocate to Spain. While the organization's main focus is to aid the integration process, knowledge of the political situation in Madrid and the home countries of the organization’s members is of crucial importance to the way the organization operates. In Spain, there are over twenty-six associations dedicated to working with Cubans. The approach to their work varies depending on the political positionality of the organization and its members. Some organizations are dedicated to the movement of solidarity among the Cubans on the island, those in Spain, and the general Spanish public; meaning these organizations not only aim to help Cubans in Spain but also work to provide aid and comprehension to the Cuban government. On the other hand, some organizations condemn the Cuban government as an authoritarian regime and work to help Cubans settle in Spain, while actively organizing political movement for the end of the regime on the island.

The existence of these organizations and their ideological polarization brings forward one of the questions that is the focus of the examination of the current paper:

1) is the political position of a cultural organization a determinant of its success in providing aid to migrant Cubans in Spain?

Moreover, I wondered about the polarization that the regional autonomy brought to Spain and how the desire to maintain and form a regional identity separate from that of Spain affected the integration process for newcomers outside of Spain into those regions. Thus, I sought to work with an organization within the Basque Country and one in Madrid to be able to draw comparisons between the two.

As we discussed in class, the concept of collective identity in Spain was the ultimate goal of integration. Prof. Toasijé pointed out that while in Spain multiculturalism is prevalent the end goal is to turn newcomers and their future generations into “more Spanish” than anything else (2024). With this in mind, I developed my second question.

2) Which organization is more effective in fostering the integration and promotion of Cuban culture in their respective regions?

Methodology

To carry out this research, I will be working with two organizations. Focusing on two different regions is crucial to understand the political polarization of the organizations as the ideology might reflect that of the host region. The first organization is the Asociación Cubano-Vasca Demokrazia kubarentzat (ACVDk), located in Bilbao, a region of the Basque Country. This organization is located in a region of Spain that holds an independent and nationalist view of their Basque identity; in this region, a person is Basque before they are Spanish (Britannica). This organization holds the anti-regime view and has taken to mobilized protests against what they refer to as dictatorship; moreover, they focus on providing social and political advocacy for their members, as well as cultural programming (ACVDk Facebook). The other is the Asociación de Amistad Hispano Cubana- Bartolomé de las Casas (AAHCBC). Located in Madrid, this organization works to build solidarity with the Cuban government and calls for the end of the US embargo on the island. This organization holds a collective Spanish identity and its autonomous community does not foster independent sentiments. Additionally, not only do they provide advocacy in social and political contexts for their members, but also focus on cultural education for Spanish citizens to learn about Cuba.

In order to mobilize the project, I will reach out to both organizations. I will explain to them the purpose and the intention behind the project and provide consent forms to the officials who speak to me. To gather data for the first question, I will generate a questionnaire that collects information on the organization's size, the political affiliation of members and donors, a summary of their services, and the frequency of their programs, as well as the political intent behind them. I will share this survey with the heads of the organizations and will conduct a correlation analysis. The information for this specific survey does not have to remain anonymous as I hope to gather it from the leading officials of the organizations.

To answer the second question, I will work with the officials to generate a post or other medium of communication informing members of the study and asking for their participation. I will generate another survey for at least ten members of each organization and ask them to rank their feelings of belonging in Spain on a scale from 1 (lowest) to five (highest), the frequency of their participation, to list the services they utilized and the resources they gathered, their political affiliation, and ultimately ask them to rank the cultural events the organization's hosts. To quantify the data I will utilize descriptive statistics through percentages. Before beginning the survey, participants must sign a consent form and their responses will be anonymous to generate more accurate answers.

Changes in Methodology

While the intent was to compare Asociación de Amistad Hispano Cubana- Bartolomé de las Casas (AAHCBC) in Madrid and the Asociación Cubano-Vasca Demokrazia kubarentzat (ACVDk) in Bilbao, there was difficulty establishing communication with the organizations' leaders and, thus, changes had to be made to the methodology of the study.

After consulting with Prof. Toasijé, the Asociación Cultural Iberoamericana Gacela (ACIG) was brought on board for the study in replacement of AAHCBC. The ACIG is a cultural organization that focuses on exposing Cuban artists and providing them with a platform to break through the art scene of Asturias in the northern region of Spain. Asturias maintains a collective Spanish identity and does not foster separatist sentiments. The association is said to be apolitical.

The participation of this new organization and the presented time constraints (as the study needed to be performed before the end of the semester) brought some changes to the methodology and the structure of the surveys. Below are listed the changes made to the methodology of the research:

1) Member participation was discarded. Time constraints presented a conflict in obtaining the intended ten participants of each organization.

2) The second survey was discarded and only the first survey remained. The survey added more questions regarding member participation and presence in the organization to attempt to address the topics lost by the erasure of the second survey.

3) Only participation by the organization leaders was expected.

Survey Structure

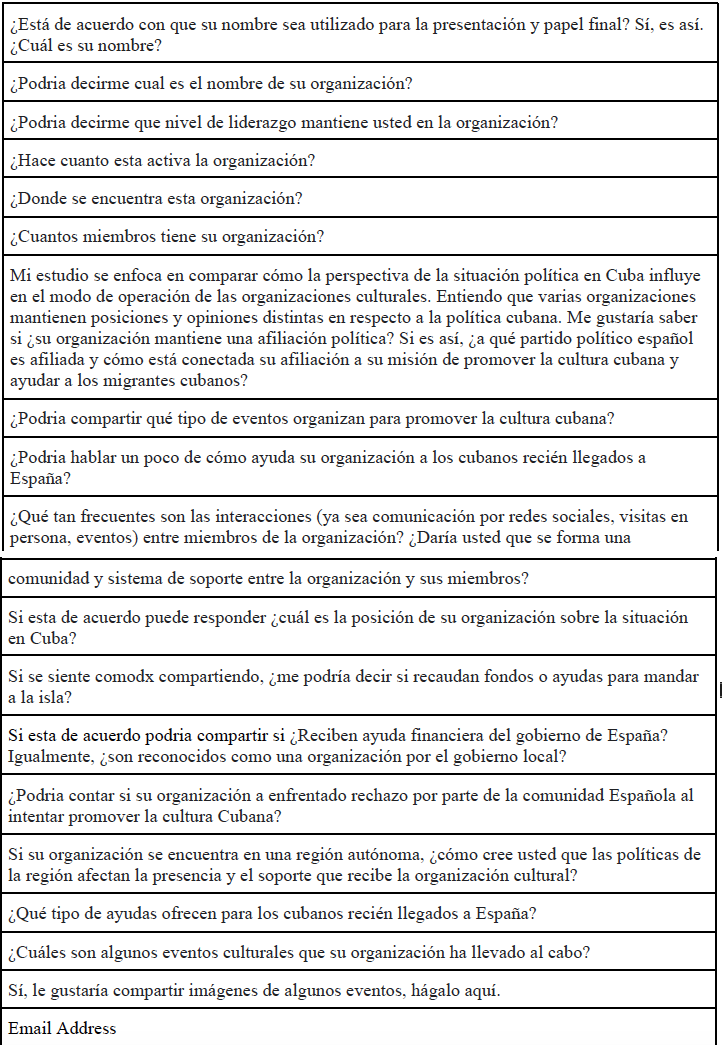

The structure of the survey focused on examining organizations' perspectives on Cuban and regional politics and the cultural events they hosted as well as the resources they provided for their members. The survey utilized in the study was composed of nineteen questions. The first two questions were focused on the organization and the role they maintaining in it. Questions three through six, eight, nine, eleven, and seventeen through nineteen focused on the effectiveness of the organizations in helping relocated Cubans find resources and integrate into Spanish culture. These questions were drawn from the review of the literature of Shields et al (2016). Questions seven, ten, twelve through sixteen, focused on the organizations' position towards Cuba and its politics, as well as the political positionality of the organization in Spain. The responders were encouraged to write short and/or long answers for each question. Additionally, the questions were written in Spanish and revised by Prof. Toasijé to ensure proper communication with the participants.

The present study is still ongoing -as participants have yet to return the forms. Therefore, I put forward the hypothesis for the study, first presenting that of the intended study in which ACVDk and AAHCBC were being compared and following it with the revised hypothesis in which ACVDk and ACIG were compared:

For question one regarding the positionality towards Cuba and the impact it had in promoting aid for recently relocated Cubans in Spain, the hypothesis establishes that Asociación Cubano-Vasca Demokrazia kubarentzat (ACVDk) will be more successful in promoting aid for recently relocated Cubans. The reason is that the Anti-Revolution sentiment aligns with a lot of political and economic organizations who fear proximity to Marxism and are more likely to invest in the organization that advocates for the fall of the Marxist political system on the island. Additionally, the ACVDk -based on their social media and self-description of events- is vocal about the “need for Cubans to leave the island.” Therefore, it is hypothesized that they would do more to aid the newcomers in Spain.

For question two regarding the success in promoting Cuban culture and integration, it is hypothesized that based on the location of the Asociación de Amistad Hispano Cubana-Bartolomé de las Casas (AAHCBC), they will have more success. The reason for this is based on the Pardo reading of Chapter 7 “Madrid’s Intercultural Perspective” which establishes Madrid as a more welcoming and intercultural region of Spain. Additionally, the Basque regionalism that exists within Bilbao is more likely to shun away the settlement of different cultures within a region/country that is actively struggling to establish itself as valid in the eyes of the Spanish government.

For question one in the revised study, the new participation from Asociación Cultural Iberoamericana Gacela (ACIG) implies a shift in the study in which the second organization is apolitical. Thus, after a revision of the literature (Shields et al, 2016), the hypothesis for question one remains the same. Asociación Cubano-Vasca Demokrazia kubarentzat (ACVDk) is hypothesized to put forward information that speaks negatively about the Cuban government, thus, drawing a bigger crowd of participation and resources from those who share anti-Communist sentiments.

The hypothesis for question two after revision puts forward the idea that Asociación Cubana Iberoamerican Gacela will be more successful in promoting Cuban culture -since they are a cultural and artistic organization that spotlights Cuban artists- however, in terms of providing resources for integration, ACVDk is more likely to be more successful as the organization directly focuses on advocating for their members socially and politically.

Limitations and Future Research

The limitations of the current study should be taken into consideration when examining the results. To begin with, in this study, the questionnaire was provided only to leaders of the organization. This could yield biased results on behalf of the responders as they might aim to paint the organization in a better light. Additionally, the lack of member involvement in the study limits the scope of understanding of how effective the organizations are in helping their members. Additionally, the open-ended questions might allow for misinterpretation when the researcher attempts to analyze the responses as the tone of the response will not be heard.

Future research aiming to investigate the subject of cultural organizations should consider incorporating the voices of members of the organizations. Furthermore, future research about Cuban relocation in Spain might also focus on comparing the case of Cuban exceptionalism in Spain and examine the success of Cuban cultural organizations in comparison to other ethnic and cultural organizations.

Results

The organizations have been unable to return the forms before the writing of this article. Their participation is greatly appreciated, as well as the time they took to meet to discuss the project with me. That being said, it is crucial to establish how the results are intended to be analyzed upon their submission. Given that a statistical and correlational analysis would no longer be conducted, due to the change in survey structure, the responses from each organization would be examined through a qualitative analysis. To answer the first question, I will analyze each response and determine the success of the organization’s efforts to help Cubans who relocated to Spain integrate and promote Cuban culture by comparing the level of outreach and consistency of events that the organization has. Additionally, pairing the consistency of the organizations’ programming with that of their political sentiment towards Cubans and their region will allow me to answer the second question of this current study.

References

Asociación de amistad Hispano Cubana – Bartolomé de las casas – "La solidaridad es la ternura de los pueblos". (n.d.). Asociación de amistad Hispano Cubana – Bartolomé de las casas – "La solidaridad es la ternura de los pueblos". Retrieved March 3, 2024, from https://www.hispanocubana.com/

Britannica, T. Editors of Encyclopaedia (2024, January 31). ETA. Encyclopedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/topic/ETA

Cook-Martín, D., & Viladrich, A. (2009). The Problem with Similarity: Ethnic-Affinity Migrants in Spain. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 35(1), 151-170.

Gates, A. B. (2014). Integrating Social Services and Social Change: Lessons From an Immigrant Worker Center. Journal of Community Practice, 22(1-2), 102-129.

Ministerio de Asuntos Exteriores, Unión Europea y Cooperación. (2022, November 16). Nacionalidad española por la Ley 20/2022, de 19 de octubre. Ministerio de Asuntos Exteriores, Unión Europea y Cooperación. Retrieved March 3, 2024, from https://www.exteriores.gob.es/Consulados/saopaulo/es/Comunicacion/Noticias/Paginas/Articulos/Nacionalidad-espa%C3%B1ola-por-la-Ley-de-Memoria-Democr%C3%A1tica.aspx

Ministerio de Inclusión, Seguridad Social y Migraciones. (2023, July 6). El número de extranjeros con documentación de residencia en vigor en España crece un 7,3% en 2022. Ministerio de Inclusión, Seguridad Social y Migraciones. Retrieved March 3, 2024, from https://www.inclusion.gob.es/w/el-numero-de-extranjeros-con-documentacion-de-residencia-en-vigor-en-espana-crece-un-7-3-en-2022

Pardo, F. (2017). Chapter 7 Madrid's Intercultural Perspective. In Challenging the Paradoxes of Integration Policies: Latin Americans in the European City. Springer International Publishing.

Shields, J., Drolet, J., & Valenzuela, K. (2016, February). Immigrant Settlement and Integration Services and the Role of Nonprofit Service Providers: A Cross-national Perspective on Trends, Issues and Evidence. Ryerson Center for Immigration and Settlement.

SITUACIÓN DE LAS PERSONAS MIGRANTES Y REFUGIADAS EN ESPAÑA. (2023). Ministerio de Inclusión, Seguridad Social y Migraciones. Retrieved March 3, 2024, from https://www.inclusion.gob.es/documents/1652165/1651235/OB_informe2021.pdf/da466f31-38d8-2ce8-4a42-5ec355cb1af0?t=1669033263318

Suárez, M. (2024, February 16). Unos 200.000 cubanos viven en España, la cifra más alta desde que existen registros. DIARIO DE CUBA. Retrieved March 3, 2024, from https://diariodecuba.com/cuba/1708118970_52911.html

Thomas, R. L., Chiarelli-Helminiak, C. M., Ferraj, B., & Barrette, K. (2016, April). Building relationships and facilitating immigrant community integration: An evaluation of a Cultural Navigator Program. Evaluation and Program Planning, 55, 77-84.

Toasijé, A. (2024). Lesson On Migration [Lecture on Migration and Diversity in Spain]. NYU Madrid.